Python getting started guide

- Input Output

- Data types

- Numbers

- Strings

- Conditionals

- Repetition

- Lists and arrays

- Functions

- File IO

- Exceptions

- Lists and arrays (part 2)

- Dictionarys

Input Output

Before getting into concepts of programming, we will look at the basics of input and output so we can create interactive programs from the start.

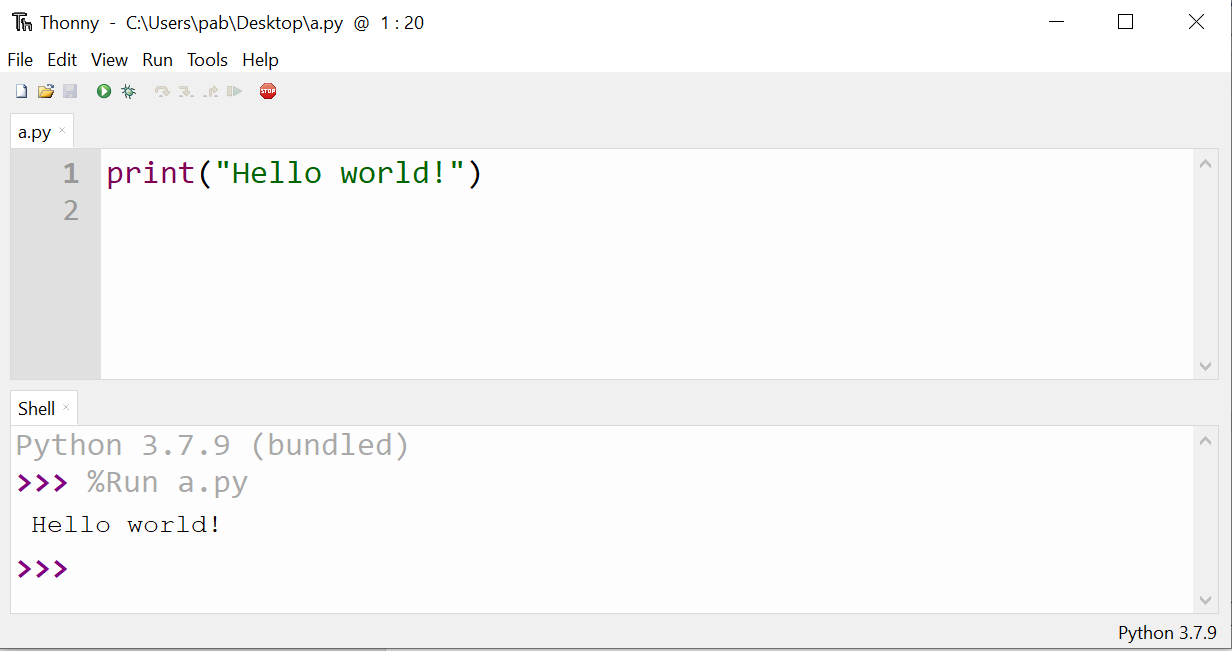

Printing

To display a message from Python use the print() function.

- Take care to use opening and closing round parenthesis, ie: ( )

- Take care to enclose your text with double quote characters, ie: “

- Write the program below

print("Hello world!")

- Save your program

- Click the run icon and your message will display in the “Shell” window.

Variables

We will now define your first variable. A variable is a named location in the computers memory. It is similar to you writing something on a post-it note, so you can refer to it again later. In the computers case, we use the name of the variable as the means to refer to it later.

This will create a variable called name and assign it the text between the quote characters. Put your name inside the quotes.

name = “Mr Baumgarten”

Important notes:

- Variables are assigned right to left. This is owing to Computer Sciences origins from mathematics.

variable_name = calculated value

Students often struggle with this when programming at first, and try to write code where the values traverse from left to right like this…

"Mr Baumgarten" = name

… but that will not work!

Programming languages are strict with their syntax and the computer will not understand what you are doing. It has been created to expect the target on the left and the value on the right. Get used to it now and save yourself the heartache.

name = "Mr Baumgarten"

-

Variable names are case sensitive.

nameis not the same asNameorNAME. -

Variable names can not contain spaces. If you wish to join multiple words together in a variable name, the Python style is to use an underscore character. eg:

person_name. Other programming languages use “camel case”, eg:personName. Stylistically, form good habits by being consistent in whatever style you use, it will make programming a lot easier for you in the long run. -

Variable names must start with a letter. After that, they can contain digits and underscores. Other punctuation characters are not permitted.

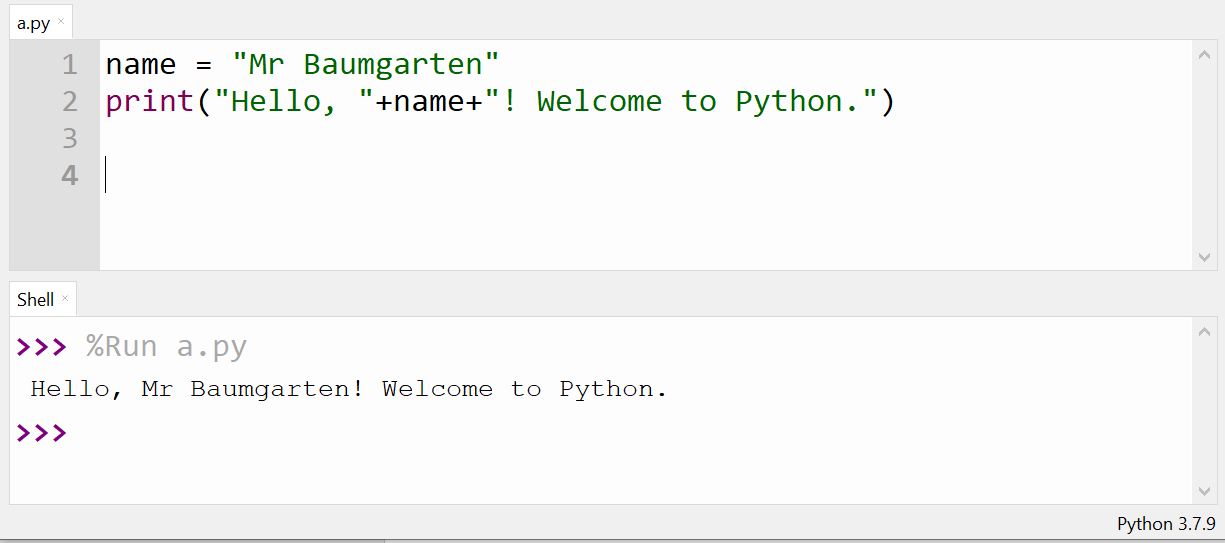

Printing a variable

Now refer to your variable in the print function. It asks the computer to retrieve the value we have stored. There are three distinct parts to the updated print() function parameters:

- “Hello”

- name (your variable)

- ”! Welcome to Python”.

The plus sign operator is instructing Python to join (concatenate) these text blocks together before they are sent to the print() function.

name = "Mr Baumgarten"

print("Hello, "+name+"! Welcome to Python.")

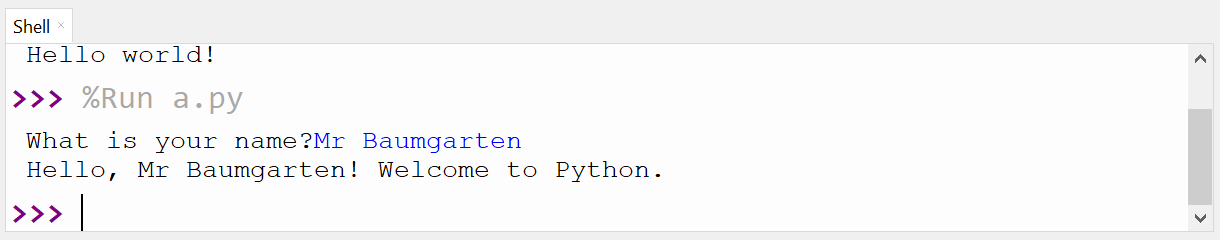

Input

We don’t just have to assign fixed content to a variable. We can have the program prompt the user to enter a value as well. To do this, update your first line of code to use the input() function.

name = input("What is your name?")

print("Hello, "+name+"! Welcome to Python.")

Data types

Computers think in binary. The data we ask computers to process in our programs need to be converted to a binary form for the computer to be able to deal with it for us. The complication is there is no one universal way of storing “everything”… because data is complicated. The tasks we will ask the computer to do with numbers (addition, multiplication, etc) are different to the tasks we will ask the computer to do with text (join text together, search the text, convert it to upper case, etc).

As a result, creating a variable, Python will also make note of the “type” of data to be stored so that it knows how to parse and process it.

Python is known as an implicitly typed language. This means, for most purposes, you do not need to explicitly tell Python which type to associate with the data. It can infer it (make a good guess) based on what is given to it. Nevertheless, these types do exist in the background, and it is important you are aware that variables will behave differently based on the typing information Python has associated with them.

The following are the main types you will work with initially.

Integer

An integer in programming is the same as the concept in mathematics. It is a real, whole number.

This line of code will create a variable, n, and assign it the value 42.

n = 42 # This is an integer ... a whole number

Float

A float (more correctly, a floating-point number) is the same as the concept of a real number in mathematics. It may contain decimals. This line of code will create a variable, pi, and assign it 3.14

pi = 3.14 # This is a float ...... numbers with decimals

The methods used to store the value of fractional numbers such as floats is complex. This is derived from seeking to store base 10 number system fractions using base 2 (binary) methods. The float is designed to maintain accuracy with respect to orders of magnitude, but it may generate some unexpected results for beginner programmers as the below illustrates.

print( 0.1 ) # Outputs 0.1

print( 0.1 + 0.1 ) # Outputs 0.2

print( 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 ) # Outputs 0.30000000000000004

Boolean

A boolean has only two possible states: True or False. Booleans become important when you start programming code requiring conditional execution (such as “if” statements or loops).

This line of code will create a variable, coding_superstar, and assign it as True.

coding_superstar = True # This is a boolean .... True or False

String

A string is shorthand for a string of characters. It is the technical name given to human readable text. Creating variables with strings involves wrapping the text in matching quotation characters so Python can clearly tell where the text starts and ends.

This line of code will create a variable, event, and assign it the text characters Code for Life.

event = "Code for Life" # This is a string of text characters

Multiple strings can be concatenated (joined) together using the addition operator

event = "Code" + " for Life" # Concatenate (join) the two strings together

See the dedicated section on strings for more detail.

Character

A character, meaning a single letter, digit or symbol of text. Python doesn’t have a way of defining characters separate to strings, so just use the normal string quotations. There are some functions we will use later that work specifically with characters.

This line of code will create a variable, character, and assign it the text character A.

character = "A" # This is a string containing a character ..... "A"

Casting

Casting is the name given to converting from one data type to another.

# Cast to integer

i = int(3) # Integer to integer

i = int(3.14) # Float to integer (truncates any decimal portion)

i = int("3") # String to integer

i = int(True) # Boolean to integer (True = 1, False = 0)

# Cast to float

f = float(3) # Integer to float, 3.0

f = float("3.14") # String to float, 3.14

# Cast to boolean

b = bool(0) # Integer to boolean, False

b = bool(1) # Integer to boolean, True

# Cast to string

s = str(3) # Integer to string, "3"

s = str(3.14) # Float to string, "3.14"

Numbers

Basic operations using raw values

print( 2 + 3 ) # addition of integers

print( 1.5 + 2.25 ) # addition of floats

print( 7 – 2 ) # subtraction

print( 3 * 4 ) # multiplication

print( 19 / 4 ) # float division, eg 4.75

print( 19 // 4 ) # integer division, eg 4

print( 19 % 4 ) # modulus (remainder), eg: 3

print( 4 ** 3 ) # exponent

Basic operations using variables

a = 100

b = 6

c = a + b # addition ... c == 106

c = a - b # subtraction ... c == 94

c = a * b # multiplication ... c == 400

c = a / b # float division ... c == 16.66667

c = a // b # integer division ... c == 16

c = a % b # modulus (remainder) ... c == 4 (remainder of 100 divided by 6)

c = a ** b # exponent ... c == 1000000000000 (ie: 10^6)

print(c)

Math constants

answer = math.pi # π = 3.141592

answer = math.e # the natural number, e = 2.718281

answer = math.inf # Infinity!

Math functions

answer = math.sqrt(100) # Square root

answer = math.pow(10,3) # 10 to the power 3, returns 1000

answer = math.gcd(104,64) # Greatest common divisor

answer = math.log(1024,2) # Log of base 2, returns 10 in this case

answer = math.hypot(6,8) # Hypotenuse of triangle with sides 6, 8

Random numbers

import random # Need to import the random library

number = random.random() # Random float from 0, up to but excluding 1

number = random.randint(1,100) # Random integer from 1 to 100 inclusive

Math rounding

# ceil() always rounds to the integer on the right of the number plane

number = math.ceil(6.4) # Returns 7

number = math.ceil(-6.4) # Returns -6

# floor() always rounds to the integer on the left of the number plane

number = math.floor(6.7) # Returns 6

number = math.floor(-6.7) # Returns -7

# trunc() always truncates (chops off) any decimal values

number = math.trunc(6.7) # Returns 6

number = math.trunc(-6.7) # Returns -6

# abs() returns absolute value, stripping away any negative sign

number = abs(6.7) # Returns 6.7

number = abs(-6.7) # Returns 6.7

# round() when .5, will round to nearest even integer

number = round(6.5) # Returns 6

number = round(-6.5) # Returns -6

number = round(7.5) # Returns 8

number = round(-7.5) # Returns -8

number = round(1.234, 1) # Round to 1 place, eg: 1.2

Trigonometry functions

answer = math.cos( angle ) # Cosine of angle (use radians)

answer = math.sin( angle ) # Sine of angle (use radians)

answer = math.tan( angle ) # Tangent of angle (use radians)

answer = math.acos( adj/hypot ) # Arc-cosine in radians

answer = math.asin( opp/hypot ) # Arc-sine in radians

answer = math.atan( opp/adj ) # Arc-tan in radians

answer = math.degrees( rad ) # Convert radians to degrees

answer = math.radians( deg ) # Convert degrees to radians

- If you have not learnt radians in mathematics, it is an alternative to degrees as a unit of measurement of angles. Programming languages typically default to radians so if you prefer working in degrees, you will need to use the conversion functions as follows:

angle = 45

ratio = math.cos(math.radians(angle)) # Cosine of angle 45°

angle = math.degrees(math.acos(ratio)) # Angle of ratio, converted to degrees

Strings

Strings are text variables. The name is shorthand for a “string of characters”.

To define a new string variable, use the assignment operator and a matching set of quotes to enclose the content. Quote characters may be single quote (‘), double quote (“) or triple-double quotes (“””).

name = 'Mr Baumgarten'

location = "Hong Kong"

website = """https://pbaumgarten.com/"""

The single quote and double quote method are interchangeable. Having the two method are useful if you wish to use the other quote style as a character within the string. Consider words with an apostrophe such as “can’t”. Using the double quotes to enclose that string means Python won’t confuse the apostrophe as an end of string quote.

text = "You can't use single quotes to open/close this string"

The triple-double quotes can be used to create multi-line strings in Python

text = """This string is valid

even through it goes over multiple lines

because it uses the triple-double-quotes."""

F-strings

F-strings are a method of merging the string representation of multiple variables together using a template. Put a lowercase “f” adjacent to the starting quote symbol and then enclose the different variables you wish to use in { curly braces }. As the example below shows, you do not have to convert from integer or other types, Python will automatically get the string representation of the variable for you.

name = "Mr Baumgarten"

meaning = 42

message = f"Hello {name}, the meaning of life is {meaning}!"

print(message)

There are some useful formatting tricks available with f strings such as:

- Specifying the number of decimal places

- Specifying the width of characters to use for right-aligned padding purposes (see next page)

num = 42 thirds = 1 / 3 print(f"Right align in a 10 character wide space: {num:10}") print(f"Two decimal places: {thirds:.2f}") print(f"Combined: {thirds:10.2f}")

Extracting characters and substrings

Strings in Python (and most other programming languages) are zero indexed. This means the first character occurs at position 0. This is relevant when you wish to extract substrings. Consider the phrase, “To infinity and beyond!”. This contains 23 characters. The following table illustrates the index value of each individual character.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

T o i n f i n i t y a n d b e y o n d !

To extract a single character,

- Attach a set of square brackets at the end of your string variable and provide the index number of the character you wish to extract inside.

character = string_variable[ index ]

s = "To infinity and beyond!"

ch = s[16]

print(ch) # outputs 'b'

To extract a substring,

- Attach a set of square brackets on the end of the variable name.

- Enclose two values with a colon character to separate.

- The first value is the index value of the first character you want.

- The second value is the index value of the first character you do not want.

new_string = string_variable[ start : end ]

s = "To infinity and beyond!"

s2 = s[3:11] # From character #3 inclusive to #11 exclusive... s2 contains "infinity"

Python will allow you to leave out the start or end value. If you leave out the starting value, Python will start from 0. If you leave out the end value, Python will go to the end of the string.

s = "To infinity and beyond!"

s2 = s[:2] # From beginning until character #2.............. s2 contains "To"

s2 = s[16:] # From character #16 to end...................... s2 contains "beyond!"

String evaluation functions

There are a number of functions available for you to query the content of a string

s = "To infinity and beyond!"

# The following return an integer for an index location

n = len(s) # get length of string ... n == 23

n = s.count(" ") # count spaces in string ... n == 3

n = s.find("o") # position of first 'o' (-1 if not found)... n == 1

n = s.rfind("o") # position of last 'o' (-1 if not found) ... n == 19

# The following return a True/False boolean

result = s.startswith(" ") # does it start with " "? (True/False)

result = s.endswith(" ") # does it start with " "? (True/False)

result = s.isnumeric() # does it contain only numbers? (True/False)

result = s.isalpha() # does it contain only letters? (True/False)

result = s.islower() # is it all lowercase? (True/False)

result = s.isupper() # is it all uppercase? (True/False)

result = s.istitle() # is it all title case? (True/False)

result = s.isspace() # is it all spaces? (True/False)

String operations

The following functions will generate a new string for you based on the content of an existing string.

s = "To infinity and beyond!"

s2 = s.lower() # == "to infinity and beyond!"

s2 = s.upper() # == "TO INFINITY AND BEYOND!"

s2 = s.title() # == "To Infinity And Beyond!"

s2 = s.swapcase() # == "tO INFINITY AND BEYOND!"

s2 = s.ljust(30) # == "To infinity and beyond! " (left justify)

s2 = s.rjust(30) # == " To infinity and beyond!" (right justify)

s2 = s.replace(" ", "--") # == "To--infinity--and--beyond!"

Common mistakes to watch for

- Mis-matched quote types - Check the quote character you start a string with is the same one you use to close a string

- Index numbers - Remember string character numbering starts at zero rather than one

- Inclusive and exclusive - Extracting substrings, the first index number is inclusive of the character you wish to extract but the closing index number is exclusive

Conditionals

An “if” statement allows our program to make decisions, and run different programming instructions as a result. It does this through a comparison operation. If the result of the comparison is “True” then the optional code will execute.

Comparison operations

Try the following to see the results

a = int(input("Enter number a:"))

b = int(input("Enter numebr b:"))

print(a == b) # Is a equal b?

print(a != b) # Is a not equal to b?

print(a < b) # Is a less than b?

print(a <= b) # Is a less than or equal to b?

print(a > b) # Is a greater than b?

print(a >= b) # Is a greater than or equal to b?

Notice:

- The equality comparison is a double-equal sign! This is to distinguish it from assignment which is the single equal sign.

Defining Python code blocks

The if statement is the first time we have having to consider Python’s unique way of defining blocks of code (sections of code we want to run together).

Python has three key rules affecting the syntax of secondary code blocks:

- The line defining the start of a code block will terminate with a colon character

- The code block must be indented in from the previous code. This indentation must be consistent. It may be spaces or tabs (Thonny defaults to converting tabs to 4 spaces).

- To end the code block, end the indentation (return to the previous amount of indentation).

a = int(input("Enter number a:"))

b = int(input("Enter numebr b:"))

if (a == b):

print("Number a is equal to number b")

print("This is a continuation of the code block")

print("As is this")

print("The indentation finished.")

print("These lines will execute regardless of the 'if' statement.")

The “if” statement

The structure of an “if” statement may be described as:

if (comparison_is_True):

executeThisCode()

executeThisCode()

elif (alternative_comparison_is_True):

executeThisCodeInstead()

executeThisCodeInstead()

else:

executeThisCodeAsAFailsafe()

executeThisCodeAsAFailsafe()

Basic “if” statement.

a = int(input("Type integer a:"))

b = int(input("Type integer b:"))

if a == b:

print("a and b are the same")

Include an “elif” and “else” condition.

a = int(input("Type integer a:"))

b = int(input("Type integer b:"))

if a == b:

print("a and b are the same")

elif a < b:

print("a is lower than b")

else:

print("a is higher than b")

Compound conditionals

It is possible to make an “if” statement conditional on the result of more than one comparison. This is called a compound conditional. The two most common compound operations you will use are “and” and “or”. You’ll learn more about logic operators later but for now:

- An “and” will be true if both comparisons are true.

- An “or” will be true if either one of the comparisons is true.

Example of “and” compound conditional.

a = int(input("Type integer a:"))

b = int(input("Type integer b:"))

if a > 0 and b > 0:

print("Both are larger than zero")

Example of “or” compound conditional

a = int(input("Type integer a:"))

b = int(input("Type integer b:"))

if a > 0 or b > 0:

print("At least one of the numbers larger than zero")

Be aware that compound conditionals require fully written comparisons on both sides of the “and/or” keyword. Below illustrates some common mistakes students make.

# INCORRECT

if a or b == 0:

if a == 0 or 1:

if a > 0 and < 100:

# CORRECT

if a == 0 or b == 0:

if a == 0 or a == 1:

if a > 0 and a < 100:

Repetition

Looping constructs allow you to design algorithms that will execute the same block of code repetitively until certain conditions are met. Python has two main looping constructs: The while loop and the for loop.

While loop

It works very similar to the “if” statement. The comparison part is written the same. The difference being the while loop will repetitively run the code block until the condition is no longer True.

The while loop is known as a pre-conditional loop in that the condition is checked before executing the loop.

while <compaisonIsTrue>:

executeThisCode()

number = 1

stop = int(input("Count from 1 to ?"))

while number <= stop:

print( number )

number = number + 1

print("The end!")

For loop

For loops in Python are designed to repeat the code over a sequence of values in a variable. The for loop is known as a count-conditional loop in that it executes the loop a specific number of times.

for <variable> in <sequence>:

executeThisCode()

A simple example

for number in [1,2,3,4,5]:

print(number)

- number is a variable (you can name it whatever you like). It is assigned the first value in the sequence and the code block is executed. The value of number is then updated with the next value in the sequence, and the code block is executed again. The process repeats until all values in the sequence have been used.

For loop with range()

It is very common to use the range() function with the Python for loop. There are three forms the range() function can take.

range( stopValue )

- Will generate a sequence of integers from 0 up until but not including the stopValue, incrementing by 1.

range( startValue, stopValue)

- Will generate a sequence of integers from startValue up until but not including the stopValue, incrementing by 1.

range( startValue, stopValue, incrementValue )

- Will generate a sequence of integers from startValue up until but not including the stopValue, incrementing by the incrementValue (which can be negative!).

Examples of each of the above options.

# Will print 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

for number in range(10):

print(number)

# Will print 5,6,7,8,9

for number in range(5, 10):

print(number)

# Will print 0,3,6,9

for number in range(0, 10, 3):

print(number)

# Will print 10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1

for number in range(10, 0, -1):

print(number)

An interactive example for you to try…

start = int(input("Count from ?"))

stop = int(input("Count to ?"))

increment = int(input("Increment by ?"))

for number in range(start, stop, increment):

print(number)

Question: What do the keywords break or continue do within a loop? Experiment to find out!

Lists and arrays

At a basic level, you can think of a list as a way of storing multiple values of data against one variable name.

The Python list is similar to the array construct found in other programming languages, though there are some important distinctions. Those taking courses such as IGCSE or IB Diploma Computer Science do need to be aware of the differences so take heed to your teachers input on that.

Defining a list

primes = [1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23]

vowels = ["A", "E", "I", "O", "U"]

characters = ["Harry", "Hermione", "Ron", "Dumbledore", "Voldemort"]

Extracting individual items from a list - Like strings, lists are zero indexed!

item = characters[0] # Will put 'Harry' into item

print(characters[1]) # Will print 'Hermione’

Mutate (change) a list item

characters = ["Harry", "Hermione", "Ron", "Dumbledore", "Voldemort"]

characters[3] = "Snape" # Dumbledore replaced by Snape

Extracting a sublist from a list

- Extracting a sublist uses the same syntax as extracting substrings.

new_list = list_variable[ start : end ]

numbers = [32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384]

subset = numbers[4:7] # Will include 512. 1024, 2048

subset = numbers[7:] # Will include 4096, 8192, 16384

subset = numbers[:3] # Will include 32, 64, 128

Querying if an item is in a list

# Is "Hermione" in the list?

if "Hermione" in characters:

print("Yes!")

For loop with lists

Remember the for loop will iterate over sequences? Well, Python will treat a list as a sequence of values you can iterate over with a for loop as well!

# Loop over every item in the list

for person in characters:

print(person)

That said, it is often very useful to know the index value of whatever item in the list you are working with. An easy way to do that is to use the range() function to generate a sequence based on the size of the list.

# Loop over every item in the list using an index variable

for i in range(len(characters)):

print(characters[i])

Add and remove items in a list

This is one of the key ways in which the Python list behaves differently to an array found in other programming languages. Typically an array is set in size for the number of elements it can contain when first defined. You would not normally be able to increase or decrease the overall number of elements like you can with the Python list.

Add an item to the end of the list

planets = ["Mercury","Venus","Earth","Mars","Jupiter","Saturn","Uranus","Neptune"]

planets.append("Pluto") # Pluto has been added to the list

Insert an item to a specific index location within the list

planets.insert(3,"Luna") # Inserted between Earth and Mars

Remove last item from the list, and return it

item = planets.pop() # Pluto has been deleted

Remove item from list based on its index location, and return it

item = planets.pop(3) # Luna has been deleted

Remove item from list based on its value

planets.remove("Earth") # Earth has been deleted

Other useful list functions

primes = [1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23]

occ = primes.count(5) # How many times does 5 occur?

idx = primes.index(5) # Index location of 5, eg: 3

size = len(primes) # How many items? 10

total = sum(primes) # Sum total of values in the list eg: 101

small = min(primes) # Get smallest value, eg 1

large = max(primes) # Get largest value, eg 23

primes.sort() # Sort into ascending order

IGCSE / IB Diploma students: Take caution using any of the above with the exception of len() in examinations. Normally these courses will be testing you to create the logic of calculating the sum, minimum or maximum, or to sort a list on your own. Using the all-in-one Python functions will be considered trivialising the problem and would not receive credit. Discuss with your teacher if uncertain.

Randomising the list

import random

numbers = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

weights = [1,1,1,1,1,2,2,2,2,2]

random.seed() # helps ensure randomness

random.shuffle(numbers) # Shuffle the list into a random order

pick = random.choice(numbers) # Select a random item from the list

pick = random.choices(numbers, weights) # Use the weights to vary the likelihood of selecting an item from numbers

Functions

We are not limited to the built-in functions of Python, we can create our own!

A function serves to create a named block of code that we can call from within our program. We can provide values for the function to work with called parameters. The function can then provide values via a return statement to the originating code that called it.

Functions come in extremely useful. They allow you to modularise your code and can make maintenance and debugging a lot simpler.

Syntax summary:

def nameOfFunction( parameterA, parameter, parameterC, … ):

codeWithinFunction()

codeWithinFunction()

codeWithinFunction()

return result

Example walkthrough

import math

def area_of_circle(radius):

result = math.pi * radius ** 2

return result

def circumference_of_circle(radius):

result = 2 * math.pi * radius

return result

def area_of_rectangle(width, height):

return width * height

def area_of_cylinder(radius, height):

circumference = circumference_of_circle(radius)

area_side = area_of_rectangle(circumference, height)

area_top = area_of_circle(radius)

return area_side + 2*area_top

area = area_of_cylinder(10, 20)

print(area)

-

The program begins execution at the line,

area = area_of_cylinder(10, 20) -

Python realises it can’t find the answer to this line on its own, that it must run the code called

area_of_cylinder()to get the result, so the main program pauses and “jumps” toarea_of_cylinder(). The value 10 is placed into the parameter radius, and the value20is placed into the parameter height. These parameters are just variables that the function can use. The variables will expire (be unavailable to your program) once the function has finished. -

While executing the

area_of_cylinder(), Python realises it must execute thecircumference_of_circle(). The process repeats, the function is paused while the other function performs its calculations.

A timeline might look like this…

area = area_of_cylinder(10, 20)

execute area_of_cylinder(10, 20)

execute circumference_of_circle(10)

return 62.8

execute area_of_rectangle(62.8, 20)

return 1256.8

execute area_of_circle(10)

return 314.2

return 1884.96

print(1884.96)

Python functions pass parameters by reference. This means it is the memory address of the variable that is sent to the function. For basic primitive data types (integers, floats, strings) this is not an issue but you might find unexpected behaviour with more complex data such as lists and dictionaries. It’s a bit more complex than this but for now think of it this way:

- Integer, float, boolean and string parameters - you can change their values within the function without affecting the code outside the function

- Lists & dictionaries passed as parameters - if you change elements inside a list or dictionary inside the function, that change will be seen in the code outside the function.

The recommended approach for beginners is to avoid making changes to parameter variables - treat them as if they are read only and create other variables within the function to perform calculations.

File IO

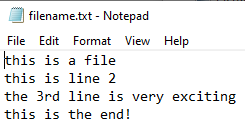

Text files

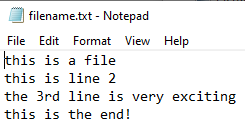

Create a simple text file using Notepad or a similar editor. We will look at how to read and write to files now.

To read a text file, creating a list of strings, with one string for each line of the file.

with open("filename.txt", "r") as f:

info = f.read().splitlines()

If you printed this list, you would get the following

['this is a file',

'this is line 2',

'the 3rd line is very exciting',

'this is the end!']

To take a list of strings and save it to a file, a new line for each string:

with open("filename.txt", "w") as f:

for line in info:

f.write(line+"\n")

- Note: The “\n” adds the end of line character

If you research file handling with Python tutorials online you will likely come across the readlines() and writlines() functions. While these do work, they probably do not behave the way you think they will, hence I haven’t used them in this guide.

CSV files

CSV files, or comma separated value files, are a common format for exchanging data between programs. You can easily create your own using Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets.

import csv

Using the spreadsheet shown above, we want to create the following output

Alice has a balance of: 59

Brittany has a balance of: 72

Charlotte has a balance of: 83

Denise has a balance of: 47

The total of all balances: 261

The recipe would look like this:

import csv

# Read CSV file into a list of dictionaries (a variable containing key/value pairs)

with open("filename.csv", "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

records = list(csv.DictReader(f, delimiter=","))

# Loop through the records

total = 0

for row in records:

# Do something with the data (note: converting Balance from string to integer)

print(row['Name'], "has a balance of:", int(row['Balance']))

total = total + int(row['Balance'])

print("The total of all balances:", total)

To save/write to a CSV file from a list of dictionaries:

with open('filename2.csv', 'w', newline='') as f:

writer = csv.DictWriter(f, records[0].keys())

writer.writeheader()

writer.writerows(records)

Binary files

You can read and write binary files as well (images, videos etc) and process the individual bytes of the file.

with open("myfile.jpg", "rb") as f:

byte = f.read(1) # Read 1 byte

while byte:

# Do something with the byte (in this case, print the hex value)

print(hex(byte)+" ")

byte = f.read(1) # Read the next byte

- The “rb” indicates to read as binary.

Other files

There are other files you may want to work with.

- To download/read files from the internet, refer to the section labelled “Requests”.

- To download/read files of JSON format, refer to the section labelled “Dictionaries”.

One important issue that arises once you start working with files is you may have errors occur such as file-not-found. Read on about how to use exception handling to make your code robust for these situations.

Exceptions

Exceptions are the error events that occur when your program is running that Python cannot recover from on its own. They will result you your program crashing out unless you provide code to respond otherwise.

Exception handling is very important when working with resources outside your programs control such as files and folders on the file system, or network communications. They can guard against “file not found” or “connection lost” issues amongst many others.

Catching generalised exceptions

try:

denominator = float(input("Please enter a number: "))

result = 100.0 // denominator

print(f"100 divided by {denominator} is {result}")

except:

print("I can't do that!")

Now I’ve shown you this, you shouldn’t do it. I’ll demonstrate why.

try:

denominator = float(input("Please enter a number: "))

result = 100.0 // denoninator

print(f"100 divided by {denominator} is {result}")

except:

print("I can't do that!")

This code looks the same as before but has one critical different. I have inserted a deliberate bug… intentionally made hard to find… can you spot it? Hint: There is a spelling error on a variable name.

This bug means no matter what the user enters when they run the program, it will fail and produce the I can't do that! message. This would become very frustrating for you - the programmer - as you won’t understand why your code is not working!

Catching specific exceptions

A better solution is to specify which errors we are anticipating and to catch those specifically.

try:

denominator = float(input("Please enter a number: "))

result = 100.0 // denominator

print(f"100 divided by {denominator} is {result}")

except ValueError:

print("That wasn't a number")

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("I can't divide by zero")

The previous code runs the exception handlers for two different types of exception, the ValueError and the ZeroDivisionError. Any other exception will still cause the program to crash, thereby alerting you there remains an issue you have not anticipated.

The trick to this is to know what exception name is required. To find it you can either run the code in such a way as to generate the error (and thus read it from the error statement that Python generates), or check the Python Exceptions documentation at the link for the description of each official exception.

Lists and arrays (part 2)

Working in 2 dimensions

Often the data we want to use with lists (or arrays) is more complex than a single dimension. Computer games, image or video manipulation, spreadsheet calculations - these problems and many others organise their data into two dimensions. The Python list can work for these use cases as well.

Consider the following data

Column

0 1 3 4 5 6

Row 0 10 11 12 14 16 18

1 22 24 25 23 24 25

2 32 30 38 37 33 35

3 42 49 45 41 48 44

This can be represented in Python as:

data = [

[10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 18],

[22, 24, 25, 23, 24, 25],

[32, 30, 38, 37, 33, 35],

[42, 49, 45, 41, 48, 44]

]

To be technically correct, rather than it being a two-dimensional list, it is more accurately a list of lists. We can iterate and manipulate each of them as any other list.

Important to note is that if you are conceptually visualising it as a two-dimensional grid, the y number will be the first index variable, and the x will be the second.

rows = len(data)

columns = len(data[0])

print(f"There are {rows} rows and {columns} columns.")

# To iterate over the entire contents of both dimensions

for y in range(len(data)):

print(f"Iterating over row {y}...")

for x in range(len(data[y])):

value = data[y][x]

print(f" - Row {y}, column {x} has value {value}")

List comprehensions

List comprehensions are a powerful feature of Python that will allow you to perform complex list processing in just one line of code. They are completely optional in the sense that you can still manually iterate over lists and perform your calculations that way if you wish. The syntax is a little complex at first so don’t stress if they take some time to understand.

The syntax is:

new_list = [ calculate(item) for item in original_list ]

As an example, if you have a list of strings that actually contain numbers (perhaps you read them in from a file or retrieved them from the internet). You want to convert that list into integers so you can perform numerical calculations…

# Without list comprehension

text_list = ["10", "21", "35", "42"]

numbers = []

for x in text_list:

numbers.append(int(x))

print(sum(numbers))

# Using list comprehension

text_list = ["10", "21", "35", "42"]

numbers = [ int(x) for x in text_list ]

print(sum(numbers))

One powerful use I find for list comprehensions is for reading data from a file and converting it into the form that I want for processing. Here is an example recipe…

# Read a text file of integers, 1 per line

with open("filename.txt", "r") as f:

content = f.read().splitlines() # creates 1d list of strings

numbers = [int(n) for n in content]

We can do list comprehensions inside other list comprehensions too in order to create 2-dimensional data!

new_list = [[ calculate(cell) for cell in row] for row in orig_list ]

Suppose you have a CSV-style file you wish to parse manually into a 2D array of floats where the file content might resemble…

63.6,67.8,83.6,93.6,67.7,6.5,69.7,34.2,59.9,14.9

97.3,88.1,24.9,24.1,58.7,99.7,9.7,34.7,61.5,90.8

79.9,90.2,66.8,66.0,55.6,90.4,88.6,62.4,4.2,62.7

80.7,1.8,48.7,28.5,60.2,73.7,71.3,99.8,81.8,93.6

# Read a text file with 2 dimensions of floats, commas between each float

with open("filename.csv", "r") as f:

content = f.read().splitlines() # creates 1d list of strings

numbers = [[float(n) for n in line.split(",")] for line in content]

Dictionarys

A dictionary is a key-value pair. They are similar to lists in that you can store multiple values against one variable name. The difference is that instead of using an integer-based index number that is automatically assigned by Python to retrieve or modify the data, you can provide your own value to refer to the individual elements with.

Dictionaries are a useful way of storing properties for different objects. Consider the example of a person. You want to store their given name, surname, email address and other contact details. A Python dictionary alleviates the need to create 10 or more separate string variables for each of these.

# Without dictionaries

surname = "Baumgarten"

given = "Paul"

email = "pbaumgarten@codingquest.io"

website = "pbaumgarten.com"

# With dictionaries

person = {

"surname" : "Baumgarten",

"given" : "Paul",

"email" : "pbaumgarten@codingquest.io",

"website" : "pbaumgarten.com"

}

To fetch individual elements from the dictionary, use the square bracket notation as with lists but supply your identifying key instead.

print( person["given"] )

To add additional elements, instead of using .append(), just create the item directly

person["youtube"] = "youtube.com/pbaumgarten"

To remove an item from the dictionary

email = person.pop("email")

To iterate over the dictionary with a for loop

for key,val in person.items(): # Iterate over the dictionary

print(key,"has value",val)

To check if a key exists

if "email" in person: # Does this key exist in the dictionary?

print(person['given'],"has an email of ",person['email'])

To convert between dictionaries and lists

# Take a dictionary and convert into two lists

keys = person.keys() # Get a list of all keys

vals = person.values() # Get a list of all values

# Take two lists and convert into a dictionary

k = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

v = ['sun','mon','tue','wed','thu','fri','sat']

days = dict(zip(k,v))

Resulting dictionary would be:

{1: 'sun', 2: 'mon', 3: 'tue', 4: 'wed', 5: 'thu', 6: 'fri', 7: 'sat'}

Dictionary comprehensions

Similar to lists, Python also has dictionary comprehensions

new_dictionary = { calc(key):calc(val) for (key, val) in original.items() }

JSON files

JSON files are a commonly used method of exchanging data between programs across networks, particularly on the internet. It is a text file format that encodes a combination of lists and dictionaries.

import json

# Read JSON file to list/dictionary structure

with open("data.json", "r") as f:

data = json.loads(f.read())

# Write list/dictionary structure to JSON file

with open("data.json", "w") as w:

w.write( json.dumps( data, indent=3 ))